On the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the activist, orator and the man once referred to in eulogy by the late Ossie Davis as “Our Shining Black Prince,” El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (most commonly known as Malcolm X), I quite foolishly decide to wade into that whole X-Men analogy thingy. Of course I’ve been warned. Of course I know better. But since when has that stopped me? So then, let’s do this thing.

On the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the activist, orator and the man once referred to in eulogy by the late Ossie Davis as “Our Shining Black Prince,” El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (most commonly known as Malcolm X), I quite foolishly decide to wade into that whole X-Men analogy thingy. Of course I’ve been warned. Of course I know better. But since when has that stopped me? So then, let’s do this thing.

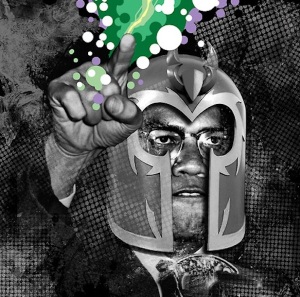

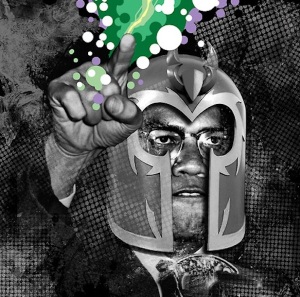

And that supremely bad ass Malcolm & Magneto mash-up art you’re seeing, is courtesy of the amazing John Jennings and his 2012-2013 exhibit Black Kirby. If yuh dunno, now yuh know.

Black Politics, White Gaze

“Malcolm X is Magneto and Professor X is Dr. King! And mutants are black folk!”

If you were black and grew up in the 80s and 90s reading or watching the X-Men, this line (in some variation) was your mantra. And for good reason. It made your love for the popular Marvel comic book something personal. Yeah most of the characters were white, but you got the symbolism–like African Orisas hiding behind Catholic Saints in those candles in the “ethnic” part of your grocery store. What’s more, it was the best selling point to family and friends on why you were so geeked about the X-Men. And it worked! You converted whole legions of black folk to your love of admantium claws and what-not because the black history tie-in was so obvious. So effortless. So seamless.

Or was it?

In recent years this popular mantra has come under criticism. Mainly, many argue that the notion of the X-Men as part of a Civil Rights allegory, complete with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King as Magneto and Professor Xavier respectfully, is distinctly wrongheaded and problematic. So is that the case? Were my childhood sensibilities somehow off? Was I (and a whole lotta folk I know) seeing things? Creating illusions rather than allusions? (I’m proud of that deft rhyme scheme by the way) Turns out, that like trying to explain to someone why the awesome Dark Phoenix Saga should never, ever, never be misconstrued with whateva the heck they were trying to do in X-Men: the Last Stand (burn it! burn it with fire!)–it’s complicated.

In recent years this popular mantra has come under criticism. Mainly, many argue that the notion of the X-Men as part of a Civil Rights allegory, complete with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King as Magneto and Professor Xavier respectfully, is distinctly wrongheaded and problematic. So is that the case? Were my childhood sensibilities somehow off? Was I (and a whole lotta folk I know) seeing things? Creating illusions rather than allusions? (I’m proud of that deft rhyme scheme by the way) Turns out, that like trying to explain to someone why the awesome Dark Phoenix Saga should never, ever, never be misconstrued with whateva the heck they were trying to do in X-Men: the Last Stand (burn it! burn it with fire!)–it’s complicated.

Back in 2011 Steven Padnick at Tor blogs was pretty blunt about where he stood in his article, “Professor X is Not Martin Luther King.” There you go. Padnick argues that Martin Luther King Jr., a peacenik, would never agree with Professor X’s outfitting of a mutant group who believes self-defense is sometimes necessary. Further, Magneto to Padnick is no Malcolm X; any such correlation he asserts, conflates “a monstrous villain with a respected civil rights leader.”

And Padnick finds ready agreement in numerous posts like David Brothers By Any Means back in 2006. In an unauthorized psychoanalysis of the X-Men genre titled Prejudice Lessons from the Xavier Institute Dr. Mikhail Lyubanksy argues near the same, stating that while such analogies are “provacative,” they are “entirely inaccurate.” Lyubanksy states that the real Dr. King never served to “shield whites” from blacks, the way Xavier works to shield humans from mutants. Further, Lyubanksy asserts that to correlate Malcolm X with Magneto is to equate the latter’s “fanatacism and terrorism” with a much more “multilayered” historical figure, which only “serves to reinforce many White fears and stereotypes about African Americans in general and Black Muslims in particular.”

No real quarrel from me here. These arguments make excellent points. Professor X and Magneto are simplistic, reductionist and even stereotyped versions of the historical Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. I also think however that in the end, that is the *entire* point. Because if anyone wants to know where this whole Civil Rights, Black Power, Malcolm & Martin analogy came from–one need look no further than the Marvel franchise and figures intimately tied to the X-Men Universe.

In more than one interview, X-Men creator Stan Lee has referenced Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr as personas for his Magneto/Professor X dichotomy. Or at the least, he has let it go unchallenged when mentioned. Even more muddling, Lee has hinted that the analogy was not direct but may have been subconscious. In a 2000 interview he stated that the X-Men were “a good metaphor for what was happening with the civil rights movement in the country at that time.” Co-creator, the late Jack Kirby, is not known to have ever spoken directly to the issue.

In more than one interview, X-Men creator Stan Lee has referenced Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr as personas for his Magneto/Professor X dichotomy. Or at the least, he has let it go unchallenged when mentioned. Even more muddling, Lee has hinted that the analogy was not direct but may have been subconscious. In a 2000 interview he stated that the X-Men were “a good metaphor for what was happening with the civil rights movement in the country at that time.” Co-creator, the late Jack Kirby, is not known to have ever spoken directly to the issue.

Marvel itself has never outright denied the Malcolm and Martin analogy. After all, being cutting edge and forward-thinking in the 1960s in dealing with real world issues is now enshrined in the brand–the X-Men and Black Panther (both created Lee & Kirby) serving as key examples.

A fitting comparison, this icon of the mythical Wakanda was created actually before the Black Panther Party of Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton. The panther symbol may have derived from the preceding Lowndes County Freedom Organization or even the famed WWII 761st black tank battalion the Black Panthers. The original T’Challa in fact isn’t all that political. But he certainly grows into the role over time. Yet it seems almost naive to believe that in the heady moment of Black Power, Kirby and Lee at Marvel were ensconced in some bubble that cut them off from such popular social currents and media imagery. What’s more, there is a way in which fandom can mold a character within the current zeitgeist. Whatever Kirby and Lee’s original intent with Black Panther, for many readers (particularly young black readers of the day) he became entangled with Huey, Bobby and the Afro-sporting, Africa-praising, dashiki wearing, Blaxploitation-watching spirit that imbued the Black Arts Movement and more.

It’s not too far-fetched to see similar dynamics within the X-Men.

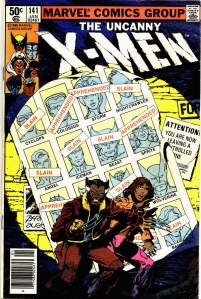

Brian Cronin at Comic Book Resources argues that despite Lee’s later claims, the original X-Men of Lee and Kirby did not fit the Civil Rights allegory. He acknowledges however that there was a shift in the X-Men universe towards a social/racial/Martin/Malcolm analogy over the years. In other words, the X-Men as characters do not remain static. Like Black Panther, they have changed and adapted with the time. They are affected by the larger social currents of their day, as new creators and fans imbue them with new perceptions.What seems agreed upon by many is that the full tilt towards the X-Men’s Martin & Malcolm persona came under writer Chris Claremont, who took over the return of the comic in 1975. The original ran from 1963-1970 and was virtually resurrected by writer Len Wein in May 1975, who introduced a more diverse team in Giant Sized X-Men #1. Wein invited the young Claremont to take over Uncanny X-Men that August in Issue #94. Claremont would continue at the X-Men’s helm for seventeen years, turning it from a barely read comic into one of Marvel’s most popular franchises. Claremont (born in 1950) was one of those young X-Men fans who came of age in the Civil Rights and later Black Power Era. The racial inscriptions in his writings seem hard to miss, and it’s during this time that the Malcolm and Martin analogy became popular to readers of his work.

Under Claremont the larger notions of X-Men facing “racial destruction” at the hands of a hateful humanity came to dominate the X-Men mythos. This is where we get the classics like “Days of Future Past” where the X-Men face a Holocaust type extinction after a virtual “race war.” It’s where the Sentinels turn into a literal mix of the Gestapo and Slave Catchers, and a lot of the X-Men’s deeper political aspirations become grounded.

In keeping up with social issues, in the 1980s Claremont even gives us Genosha–a society modeled on South African apartheid where mutants are enslaved and live their lives as oppressed citizens…located quite purposefully in the X-Men world off the coast of SE Africa. In the end, its citizens are exterminated in a mass genocide. As Claremont himself stated, “The X-Men are hated, feared and despised collectively by humanity for no other reason than that they are mutants.In the 1982 Claremont classic God Loves, Man Kills, the story starts off with the literal lynching of two black mutant children (seriously, they are *lynched*) deploys the words “nigger-lover,” has an anti-mutant hate group called Purifiers modeled blatantly on white supremacists (complete with a type of Celtic Cross symbol) and has Magneto at perhaps his most Malcolm X-esque.

This “racial symbolism” would stamp the X-Men during what many consider its “Golden Age” and influence writers/creators/readers to present day. No wonder that when director Bryan Singer signed on to do the first X-Men movie, he repeatedly gushed in interviews about how this would be a classic tale of the “conflict” between Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. To make it blatantly clear, he even has Magneto declaring “By Any Means Necessary” as his final lines in the flick.

This “racial symbolism” would stamp the X-Men during what many consider its “Golden Age” and influence writers/creators/readers to present day. No wonder that when director Bryan Singer signed on to do the first X-Men movie, he repeatedly gushed in interviews about how this would be a classic tale of the “conflict” between Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. To make it blatantly clear, he even has Magneto declaring “By Any Means Necessary” as his final lines in the flick.

So the analogy is certainly not the creation of just fandom. It’s long been part of the franchise, either subtle or blatant. The question often asked is, was this the original intent? But really, does it even matter?

We don’t have Jack Kirby to answer, so Stan Lee’s conflicting statements are what’s left. Perhaps in the end it was just coincidence, as Lee sometimes alludes. But, as with Black Panther, it seems a stretch to think that sitting there in 1963, Lee and Kirby were oblivious to the goings on sweeping the country. And they created a comic book about “difference” and “oppression” wholly divorced from the political/social workings of the day. I find that about as hard to believe as I do that Hegel’s master-slave dialectic wasn’t influenced in great part by the Haitian Revolution. Like Susan-Buck Morss asserts, “Hegel knew”…and I think about the same for Lee and Kirby. They knew.

It could also be that Lee & Kirby only drew in part on the Civil Rights Era, as they also pulled on other histories of oppression. Magneto after all is tormented by the ghosts of Nazi Germany, not Mississippi. And over the years, contemporary issues of discrimination and difference have been imbued within the X-Men universe. Today the analogy often referenced for the X-Men is one of sexual orientation and “othering”–showing once again how malleable the characters are to the spirit of a given age. It may also show how much the Civil Rights era has become a fulcrum on issues of difference in our society–and why so many real life groups have modeled their struggles on this template. These are after all shared histories. In the X-universe, the deadly and very man-made Legacy Virus (which to many fans in 1993 showed analogies to HIV/AIDS) seemed to pull on conspiracies out of both the LGBQT and African-American communities. So it could be that Magneto and Professor X were only partially based on Malcolm and Martin, and that the X-Men are stand-ins for the larger human question of “how do the oppressed deal with their oppression, and how may it affect them in turn?”

It could also be that Lee & Kirby only drew in part on the Civil Rights Era, as they also pulled on other histories of oppression. Magneto after all is tormented by the ghosts of Nazi Germany, not Mississippi. And over the years, contemporary issues of discrimination and difference have been imbued within the X-Men universe. Today the analogy often referenced for the X-Men is one of sexual orientation and “othering”–showing once again how malleable the characters are to the spirit of a given age. It may also show how much the Civil Rights era has become a fulcrum on issues of difference in our society–and why so many real life groups have modeled their struggles on this template. These are after all shared histories. In the X-universe, the deadly and very man-made Legacy Virus (which to many fans in 1993 showed analogies to HIV/AIDS) seemed to pull on conspiracies out of both the LGBQT and African-American communities. So it could be that Magneto and Professor X were only partially based on Malcolm and Martin, and that the X-Men are stand-ins for the larger human question of “how do the oppressed deal with their oppression, and how may it affect them in turn?”

Still, whatever the original intent in 1963, the X-Men’s relationship to the Civil Rights/Black Protest era certainly became firmly established later on–especially by younger writers like Claremont, whose lens of oppression lay mostly in America’s black/white racial turmoil. Cronin in fact argues that Lee’s claims to the Martin and Malcolm analogy are his way of taking credit for the popularity of the Claremont era, thus allowing the comic to have one seamless continuation from start to present day. As recent as the 2011 X-Men movie First Class, the stars of the film were referencing the Martin and Malcolm duality, as reported in the April 26 edition of the LA Times:

‘X-Men: First Class’ star: MLK and Malcolm X influenced our story

How’s this for unexpected territory in a superhero film: “X-Men: First Class” not only uses the Kennedy years, the Civil Rights movement and the Cuban Missile Crisis as a backdrop for its retro tale, the movie’s story of two massively powerful mutants who struggle against bitter prejudice was directly informed by the complicated lives of Malcolm X and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“It came up early on in the rehearsal period and that was the path we took,” says Michael Fassbender, who stars as the emotionally scarred Erik Lehnsherr, who will become the militant mutant known as Magneto. “These two brilliant minds coming together and their views aren’t that different on some key things. As you watch them you know that if their understanding, ability and intelligence could somehow come together it would be really special. But the split is what makes them even more interesting and tragic.”

And here we come to what may be the crux of the matter: the perceptions of Martin and Malcolm in the minds of white society and how they fit within the larger American memory.

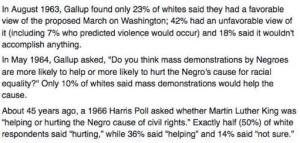

Again, the criticisms that Magneto and Professor X hardly behave like Malcolm and Martin are quite valid. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X are certainly not the one-dimensional characters portrayed in the X-Men. Most notably, Malcolm X is not really comparable to a figure twisted by past wrongs into a villain who leads a “Brotherhood of Evil.” The notion of Martin Luther King Jr. as a “dreamer” also manages to entrap his complexity within one moment (and one speech) in time. The question is, why have comic creators (perhaps Stan Lee; more assuredly Chris Claremont; definitely later movie directors and actors) found it so easy to think of both historical figures in those reductionist terms?It may have to do with many of us taking a modern liberal reading of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X as static, unchanging and universal. This however is hardly the case. Martin Luther King Jr. during his life wasn’t a universally revered icon. Even in the north, he was viewed as a troublemaker and a nuisance by much of the mainstream press. Both Newsweek and TIME only covered the Montgomery boycott belatedly, and even then reported more on the ways in which white Southerners were being inconvenienced. During the historic events in Birmingham, many in media blamed King for stoking violence and placing children in harm’s way of dogs and fire hoses. President Kennedy himself found King’s activism at times troublesome for his own domestic agenda, sending Robert Kennedy at one point to urge against the March on Washington. Jacqueline Kennedy was even more blunt, in personal recordings calling King “phony” and “tricky”, and claiming, “I just can’t see a picture of Martin Luther King without thinking, you know, that man’s terrible.”

It was not until after the March on Washington that magazines like TIME changed their tune, nominating the man they once ignored as Man of the Year–a love affair that fell apart dramatically after King spoke out against the Vietnam War. Despite the rehabilitation of the Civil Rights Movement in popular American memory today, King and black protests as a whole were hardly popular to many whites of the day:

Malcolm X to much of the press was indeed a villain incarnate. Starting in 1959 with Chris Wallace’s CBS expose “The Hate that Hate Produced,” Malcolm X was painted as a racist radical with a hatred of whites. Even after his break with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X was depicted as a fanatic, at best a sensational firebrand whose provocative words sold papers and brought in audiences. J. Fred MacDonald in his 1992 book Blacks and White TV: African-Americans in Television Since 1948, noted that, “except for a few black-hosted programs long after his assassination in 1965, television… portrayed Malcolm X as a hate-filled, racist radical.”

Malcolm X to much of the press was indeed a villain incarnate. Starting in 1959 with Chris Wallace’s CBS expose “The Hate that Hate Produced,” Malcolm X was painted as a racist radical with a hatred of whites. Even after his break with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X was depicted as a fanatic, at best a sensational firebrand whose provocative words sold papers and brought in audiences. J. Fred MacDonald in his 1992 book Blacks and White TV: African-Americans in Television Since 1948, noted that, “except for a few black-hosted programs long after his assassination in 1965, television… portrayed Malcolm X as a hate-filled, racist radical.”

These one-dimensional portrayals became part of popular American ideas of both men. Following his death, Martin was re-shaped into an American hero, his more radical anti-war and anti-poverty side omitted in favor of an eternal “dreamer.” Re-imagined as well was the myth of his mass acceptance, with his lengthy FBI file almost deleted from public memory. To complete his sainthood however, he required a foil–which was found conveniently in Malcolm X. Contrasting the two men in very one-dimensional terms become common, in both popular culture and education: the integrationist versus the separatist; a message of love versus a message of hate.

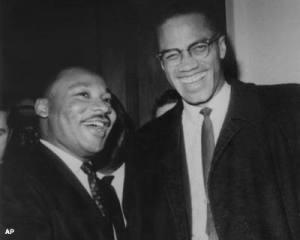

It was the more radical activists and academics who rescued Martin and Malcolm from this simplistic binary fate. In the late 1980s thru early 1990s, Malcolm X found resurgence as a hero among black youth culture–especially Hip Hop, where his speeches laced songs and his face appeared on t-shirts and posters. For these admirers, the points of convergence between Martin and Malcolm were more important than their differences. Spike Lee’s use of the photo of their embrace in 1989’s Do the Right Thing (the product of a mere chance encounter), became the ultimate symbol of this reconciliation. By the time of Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic Malcolm X, a more nuanced interpretation of the radical leader had filtered into popular society. The culmination of this transformation came in 1999, when the US Postal Service–in an act of mind-boggling co-option–unveiled a postage stamp of Malcolm X. To think, just a decade earlier Public Enemy had declared in “Fight the Power” that “none of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps.”

Professor X and Magneto are indeed faulty and inaccurate portrayals of Martin and Malcolm; but at the same time they may be *truthful* portrayals of how American society has long perceived both men. Why would anyone assume that Stan Lee or Chris Claremont, who grew up in the era of these one-dimensional portrayals, would have more nuanced modern ideas? Even the most recent present day filmmakers haven’t caught up. The question here is then, what do such problematic analogies say about popular analyses of the wide spectrum of black political thought, namely black radicalism? How do we view that part of our history, with all the implications of race it holds, in our national memory? And why are we more comfortable with simple binary dichotomies than nuanced complexity?

Professor X and Magneto are indeed faulty and inaccurate portrayals of Martin and Malcolm; but at the same time they may be *truthful* portrayals of how American society has long perceived both men. Why would anyone assume that Stan Lee or Chris Claremont, who grew up in the era of these one-dimensional portrayals, would have more nuanced modern ideas? Even the most recent present day filmmakers haven’t caught up. The question here is then, what do such problematic analogies say about popular analyses of the wide spectrum of black political thought, namely black radicalism? How do we view that part of our history, with all the implications of race it holds, in our national memory? And why are we more comfortable with simple binary dichotomies than nuanced complexity?

In Stan Lee’s defense, he always stated he originally intended Magneto not to be a villain–though that’s where the comic eventually took him. Over the years Chris Claremont also makes Magneto a more complex character, who from time to time forms alliances with Xavier’s X-Men to fight against the greater oppression mutants face. For a while, Magneto shifts from villain to perhaps good guy, finally arriving at anti-hero. It was almost as if through Magneto, Claremont was trying to figure out his own conflicting views of Malcolm, black radicalism and oppression–spilling those musings onto the pages of his comic books. And it was this mix of contradictions, binary conflicts and sometimes brilliant, but too often ham-fisted, attempts at race analysis that young fans like myself readily devoured.

Over at the blog Musliem Reverie, the analogy of Martin and Malcolm to Professor X and Magneto is skewered with well-made points that are hard to disagree with. And blogger Orion Martin cuts to the chase on the whole thing and asks why the need for all the “symbolism” and run-around in tackling the race issue so obvious in the X-Men? Martin lays it all bare on the table and asks directly, What If the X-Men Were Black?

As a black kid growing up, I was both fascinated yet put off by the whole analogy. It was a mental minefield that I had to wade through with each reading. On the one hand, I was ecstatic that these two icons were part of a comic book I so enjoyed. When and where else was I going to see Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and issues of race so obviously on display? It drew me to the comic and made me an X-fan for life. I even stuck around after that whole House of M, Wanda Maximoff, “No More Mutants,” fiasco. I mean, what the entire f—??

As a black kid growing up, I was both fascinated yet put off by the whole analogy. It was a mental minefield that I had to wade through with each reading. On the one hand, I was ecstatic that these two icons were part of a comic book I so enjoyed. When and where else was I going to see Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and issues of race so obviously on display? It drew me to the comic and made me an X-fan for life. I even stuck around after that whole House of M, Wanda Maximoff, “No More Mutants,” fiasco. I mean, what the entire f—??

On the other hand, there was never a time I wasn’t troubled by the one-dimensional portrayals. This wasn’t the Malcolm or Martin I knew. Nor were these realistic portrayals of the Civil Rights or Black Power Movements. They were someone else’s caricatures, some twisted, just off-kilter version of history that did not speak with my voice. It was someone else’s voice, a bit of racial ventriloquism–only in tights and with superpowers. But what was I to do? This was the speculative world that I was presented with. I could discard it completely or I could try to deal with it. So as with so much else in genre, I merely re-imagined and reinterpreted things to suit my own psyche. I found myself often rooting for Magneto, and having lots of empathy for his point-of-view. Even when he was made out to be the bad guy, I found a way to take his side. He had damn good cause to not trust humans. He was mutant and proud! And I understood exactly why he wanted to create a separatist haven on some far-off asteroid. For me “Magneto was right” long before it became a slogan.

There wasn’t too much contradiction in Professor X as Dr. King having a defense force like the X-Men for me, because he was never the simple “dreamer” of popular depictions in my mind. The Dr. King I knew, as journalist Charles Cobb has recently pointed out, at one time (early on) carried a gun and was protected by a cadre of folk who did the same. He at once preached non-violence, but also knew quite well “That nonviolent stuff’ll get you killed.”

There wasn’t too much contradiction in Professor X as Dr. King having a defense force like the X-Men for me, because he was never the simple “dreamer” of popular depictions in my mind. The Dr. King I knew, as journalist Charles Cobb has recently pointed out, at one time (early on) carried a gun and was protected by a cadre of folk who did the same. He at once preached non-violence, but also knew quite well “That nonviolent stuff’ll get you killed.”

Like Spike Lee and others who tried to find commonality between Martin and Malcolm (even if at times forced), the story lines I enjoyed most were when both mutant icons had to join forces to ward off some greater threat. My villain was never Magneto–it was Sentinels, Purifiers and a larger world out to oppress, enslave, marginalize and destroy mutant kind. I knew that world and that history all too well.

So in the end, of course Martin and Malcolm aren’t Professor X and Magneto. But heck, Martin and Malcolm in the popular memory of America aren’t themselves either. Nor are the Civil Rights or Black Power Movements that shaped so much of America. They’ve always been something else, something cartoonish, made-up, refitted and half-remembered. When someone (usually black) gives us anything more daring, it tends to make lots of people uncomfortable. Exhibit A: Director Ava DuVernay‘s Oscar-snubbed Selma, with a strong, forceful King, a cameo by a nuanced Malcolm X, a watered-down LBJ and nary a white-savior in sight. When we start accepting more realistic visions in our real life understanding, perhaps it will filter on down to the comic books–which only reflect us in turn. But for now the X-Men universe is the one we got, because it’s the one we’ve made. And with all its possibilities, illuminations and glaring faults, it’s perhaps one of the best lens to examine our own very real perceptions.

*This post can probably be read in conjunction with a prior blog on Race and Comic Books.

*This post can probably be read in conjunction with a prior blog on Race and Comic Books.

The Comics Journal interview with Jack Kirby:

“[Gary] GROTH: How did you come up with the Black Panther?

KIRBY: I came up with the Black Panther because I realized I had no blacks in my strip. I’d never drawn a black. I needed a black. I suddenly discovered that I had a lot of black readers. My first friend was a black! And here I was ignoring them because I was associating with everybody else. It suddenly dawned on me — believe me, it was for human reasons — I suddenly discovered nobody was doing blacks. And here I am a leading cartoonist and I wasn’t doing a black. I was the first one to do an Asian. Then I began to realize that there was a whole range of human differences. Remember, in my day, drawing an Asian was drawing Fu Manchu — that’s the only Asian they knew. The Asians were wily…” From The Comics Journal #134 (February 1990) [http://www.tcj.com/jack-kirby-interview/6/]

Good find. And I’ve heard this from Kirby before. Kind of goes to my point tho… my curiosity about *what else* might have been an influence? Kirby arrives at the novel idea that he needs “a black” in the middle of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, not to mention the anti-colonial movements sweeping Africa. Too much convergence there to rule out external influences!

Reblogged this on Fábio Kabral.

thanks for the repost!

Reblogged this on Miriamspia's Blog.

thanks for the repost!

Reblogged this on lellone.

This was… Wow. Detailed, and impassioned. Long, but you never lost your pacing. Oh, and I agree with all of it too.

Thanks for reading! It got much longer than I intended. LOL But the words kept coming. Glad you stuck in there for the read. And thanks for the reblog!

Reblogged this on Deprevation and commented:

Love This.

I love this blog you did a good job

Thanks! This spot lets me run my mouth at length. Appreciate the reblog!

Reblogged this on Seeing ears and hearing eyes .

Reblogged this on dawi94.

Reblogged this on Mobile world.

Reblogged this on .

This is heavy… Thought provoking and very necessary! Thanks for putting this out there!

Thanks for reading! I hoped to provoke thoughts!

Great blog!

Reblogged this on Life begins at 19!.

Reblogged this on wildboywiz's Blog.

Right on my man! It’s inspiring to see such passion and intelligent pieces of literature being written with such rectitude!

I love X-man, and being a young Blackman this really does tickle some thought process and invokes a hint of curiosity. Yet the way you write, i don’t even want to look into it, i just feel like you must be right in what you write.

This was was an excellent piece! Something i think every literary spelunker should trek upon just once.

Keep it up!

Word! Thanks for reading and the compliments. LOL Glad my points were convincing, but please–look into it! I always welcome new perspectives.

Reblogged this on Naijafreetree's Blog and commented:

The Activist…

Thanks for the reblog!

Reblogged this on imaz78.

Reblogged this on mishal m7.

Reblogged this on collism's Blog.

Nice one

Reblogged this on Exploits of my mind and commented:

Most of my blogs will cover my fantasy and Sci-fi writing. Yet it’s very important for a writer to also read. They need to scout out competition, healthy of course, and they need to keep themselves educated and creative. Reminding themselves of other talent out there. I once used that excuse on video games, claiming that video games inspired me, so much more so than reading. Was i ever wrong there. If you want to write and you use this video game excuse, give it up. You need to read. I’m not saying shun gaming, i still play video games, but i now put more time aside for reading. If i get the urge to game, i read no less than 10 pages of a novel, if i still want to game i will pick it up for an hour and then read again. Most of the time i don’t put it down after 10 pages though.

So while i make sure to pick up a good book 2/3 times a month, depending on the books thickness. (My next book is ‘Dreamcatcher’- Stephen King.) I find it’s also important to see what others are doing in the literary community. A place where we can all share our opinions in a more, philosophical and liberal environment.

I find myself coming across many good blogs, blogs i think many of us should see. So every so often i find it important, for myself, to reblog some powerful post. If i have any fans out there, maybe this will be a reflection of what i like to read. For those just stumbling through, maybe it will encourage you to read some of these other adroit writers next.

‘Time travel on facebook,’- Michelle at the green study. I didn’t reblog this, but it is a great piece. I enjoyed seeing how she reflected herself with facebook and what she gained from it’s unique ability to connect all over the world. I thought she did a very great job in constructing the piece and it kept my attention the whole way down.

This piece here, caught my eye as well. ‘On Malcolm, Martin and that X-men Analogy Thing.”- The Disgruntled Haradrim. A longer piece of inspiring work that is articulated with such passion and driven with such sagacity that you can’t help but empathize.

I hope you enjoy it as much as i have. Also, if any of you like Hozier- Take me to church. Check out Hozier- Jackie and Wilson. One of those catchy tunes i listened to last night while i was writing, and woke up this morning singing.

Chow.

thanks for including me on your list of writers! honored!

Pingback: On Malcolm, Martin and that X-Men Analogy Thing | Exploits of my mind

Reblogged this on esperancebetty and commented:

I love this …

thanks for the reblog!

Well-written and an enjoyable read

60s, 70s and 80s person here. I was in grade school when JFK and RFK were killed and probably the same for MLK. I remember the teacher telling us of the death of JFK in Dallas and we were in Texas at the time.

Extremely well composed and comprehensive piece.

I love your blog…

Thanks everyone who has left a comment. When you’re freshly pressed the response is kind of overwhelming, so I probably won’t be able to reply to everyone–but thank you ALL for reading and liking the post! Lots of X-Men fans out there!

Malcolm X is Magneto and Professor X is Dr. King! And mutants are black folk!”

If you were black and grew up in the 80s and 90s reading or watching the X-Men, this line (in some variation) was your mantra. And for good reason. It made your love for the popular Marvel comic book something personal. Yeah most of the characters were white, but you got the symbolism–like African Orisas hiding behind Catholic Saints in those candles in the “ethnic” part of your grocery store. What’s more, it was the best selling point to family and friends on why you were so geeked about the X-Men. And it worked! You converted whole legions of black folk to your love of admantium claws and what-not because the black history tie-in was so obvious. So effortless. So seamless

Great post! Very informative!

This is a pretty cool analysis.

Awhile back, a wordpress blogger did an issue by issue synopsis and review of the Silver age X-Men, and until then I never knew that the X-Men really hadn’t been big on social commentary and mutants weren’t part of some racial/cultural metaphor until much later. For the first era of their run, it was just your typical silver age superhero team, beloved by the by the public and with a slew of dull 1-dimensional villains (Magneto included). Sure, things changed a bit when it was relaunched with giant #1, but that was long after the darkest days of the 1960s civil rights struggle. Positioning X-Men as a Civil Rights metaphor was some clever revisionism on the part of Marvel’s creative team, and there are some great stories, great characters and worthwhile lessons in the subsequent eras of X-Men, but damn if the trope of Magneto as Malcolm X and Prof X hasn’t colored our view on race and the civil rights struggle strange ways.

To me, though, the place where the X-Men race metaphor falls apart is that sure enough there aren’t black folks blowing stuff up with super powers; like, man, it’s not that your skin color is different, it’s that you’re 10 feet tall and shoot radio-active beams out of your face and that actually IS an existential threat to society.

Thanks for the comments! And you bring up a *great* point about the probelmatics of using mutants as a metaphor for race–or any other marginalized group. Black people don’t have the ability to shoot destructive beams from our eyes or the ability to create iron skin. The notion that “normal” human might fear the powers of mutants is at least reasonable. Black people however have no such power; we’re just “normal” humans too. There have been similar questions about this approach in other speculative fiction works–namely how well the use of vampires work (or don’t work) as stand-ins for LGBTQ communities and issues in the book/television series True Blood. Thanks again for making that point.

Nice post…

Pingback: On Malcolm, Martin and that X-Men Analogy Thing | arty6530's Blog

Reblogged this on arty6530's Blog.

Reblogged this on wwwkikirikigrga.

Great comparison and interesting read. By showing us this particular case study of X-Men, we could experience a journey which transformed one of the most popular comic series to be more human. I believe that the struggle between mutants and mine is actually the best thing about the whole thing. The last X-Men movie was a blast.

What a brilliant and thoughtful post. I’ll try again with the X Men, I think.

Reblogged this on Pixel Fest.

Well written… Good read. Unfortunately perception is reality… Whether that reality is another man’s delusion or not… Ironically enough I never envisioned the two leaders as being compared to Malcolm and Martin… Perhaps that was do to my naïveté but the thought never crossed my mind…

Reblogged this on The Soul of A Woman.

Reblogged this on Woman, Child, Style and commented:

great read!

Reblogged this on theblackvanguard and commented:

Great Article

This is great.

Reblogged this on BRL MUSIC.

Reblogged this on Baron von Renteln.

Reblogged this on tides 'n' tudes and commented:

It never occurred to me that the X-Men could be read as anything other than an analogy for civil rights. Well written!

Reblogged this on Breeze6's Blog.

Reblogged this on bartopia and commented:

Such an informed opinion on a topic I’ve been guilty of accepting without further thought.

Again, thanks all for the comments and definitely for the reblogs! This post has been shared in more circles than I first imagined it would be–and that’s great!

Reblogged this on RAREBREEDZ.

Phenomenal read. I loved it!

Reblogged this on simplytiff331 and commented:

Loved this!

thanks! for the love and the reblog! 🙂

The comparison is interesting but the validity is rather superficial.

But there are other comparisons that can be made in science fiction.

What about the Narn and Centauri in Babylon 5? Could G’Kar be compared to Malcolm X with his “conversion” by going to Mecca.

How about The Uplift War by David Brin being like The White Man’s burden? LOL

Sorry, I’m to old for comic books.

on you being “too old for comic books,” i can tell. LOL. the comparison on the X-Men is kind of already old hat. If you read the piece, you’ll see i point to filmmakers and figures associated with Marvel who attest to this. so fans aren’t suffering some mass delusion. only question is *when* the comparison began; that it’s long existed is about as common knowledge as water being wet.

ironically, i remember G’Kar and Londo often being compared by fans to Prof X & Magneto. of course both B5 characters are set in a far flung future, not in our very contemporary society where issues of difference/othering are being so explicitly explored as with the X-Men. and (you’re about to get a “well actually”), most analysts of Brin’s Uplift trilogy readily point out he’s using the “white man’s burden” in his allegory of interactions between patron and less developed species. colonization in fact remains a key metaphor explored often in sci-fi–from Wells rather blatant critique of the New Imperialism of the late 19th c. with War of the Worlds (redone repeatedly in genre to play on our colonialist fears) to Silverberg’s Downward to Earth, which seems to draw a great deal on Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. all of this is kind of the point of my post—that we often explore our own world through the lens of speculative fiction. what that lens tells us about ourselves (our perspectives, bias, assumptions) is what i find interesting.

thanks for the comments!

Reblogged this on The R.R.A.P. Magazine and commented:

As a comic geek this is immensely fascinating to me

Pingback: Preach! – article round-up | The Logan Institute for the Study of Superhero Masculinities

This. Dammit, all of this and then some.

Pingback: Manifesting supervillains…pow pow | lindsay bess's electro pen & pad

i was in search of an article to buttress my belive that emergence of malcolm x and the numerous members of nation of islam with X substitute for their unknow ancestral names inspired stan lee and jack kirby to create the superhero group with almost the same problems and opinions as malcolm x team members. X MEN was created at the zenith of MALCOLM X world wide popularity

Pingback: Analogía entre los X-Men, Martin Luther King y Malcom X | Afroféminas

Pingback: The X-Men and Discrimination | ComiCommand

I’m in a History of the Civil Rights Movement class and I stumbled across this a while ago but never read it. I just finished it and e-mailed it to my professor. Thank you for the detailed and fascinating read. I know much more about comic books than Malcolm X (although I’m working on it), and I didn’t grow up black or in the 90’s, so I was only peripherally aware of the analogy. This was great.

Amye,

Thanks for reading! Happy I was able to find a way to marry your interest in comic books with your history class.

First, this was a great read.

Secondly, I find it strange that someone get offended by the comparison. Really, Magneto himself was NOT an out and out villain. He was a man with power suffering from the tragedy of surviving the holocaust. You also have to keep in mind that even IF PX and Magneto were based on these two civil rights leaders, it doesn’t mean that they would remain stagnant in thoughts and personalities. X-Men is fiction and they aren’t out to create exact replicas of anyone.

However, it was the basic philosophy alone that warrants comparison. That PX believed we could all live together while Magneto bought into the idea that his kind was the superior race. Equality vs a struggle for power. That’s where it begins and ends.

But isn’t that enough. The idea that X-Men can spark conversation about prejudice and bigotry is a good thing. It also does it in a way that relates ANY and ALL who are treated poorly for being different.

This was a great article. Thank you for sharing this.

Pingback: Chattr - AKA Every Cell in my Body

I came here because I’m was assigned to talk about the I have a dream speech and and it’s effectiveness, I had heard about the theory of what inspired x-men and went looking. I’m very grateful that you chose to write so well on the topic, this is what I was looking for. It appears you did what I’m hoping to do with my paper, look past the way MLK is portrayed and talk about how he is viewed at the time.

I really love this quote:

So in the end, of course Martin and Malcolm aren’t Professor X and Magneto. But heck, Martin and Malcolm in the popular memory of America aren’t themselves either. Nor are the Civil Rights or Black Power Movements that shaped so much of America.

Somehow I will work at least part of that into my paper, citation already made and ready to go.

Thank you so much for your insite, off i go to do some more research, because even though you seemed to look at it from all sides, i want to see if there is one you are missing.

Glad the blogpost was helpful!

Pingback: Missing The Point: Race in the Cinematic Universe of Marvel Comics – The Blerdy Report

Pingback: How allegory in sci-fi can narrow representation – Oncenerd

Pingback: Episode 5: X-Men Matters…But Why Tho? | But Why Tho? the podcast

Great piece, as a young black kid growing up watching the X-men ive always had this connection with it on a deeper level then just any other morning carton. it was clear as day who the mutants represented in reality no matter what color the individual mutant had. conscious or subconscious by the creators the mesesge is clear. i mean if you think about it look at all the hate and crimes along with slavery and genocide that was committed against african americans ONLY because the color of our skin. i mean damn we may as well of had super powers that would possibly be a threat, for how we are treated by the public and especially the police. the color of our skin is enough to be labeled a threat and criminal. so yea with that said i feel you on this article my brotha aha no the X-men nor proffesor X or Magnetto are complete depictions of the civil rights movement or Malcolm and Martin but as you said may be a perfect depiction of how we may have been perceived by the public.. Mutants

Thanks for a very informative article. I was wondering whether the X-Men were based somehow on classical archetypes (like the elements, as with the Fantastic Four) or on mythology, but I see how they can actually be political vehicles. Makes sense!

Thanks for reading! Let me say this, don’t think I’ve gotten any definitive answers on the creation of the X-Men or the X-Universe! I think the Civil Rights Movement played some role (at least definitively with Claremont), but lots of other things like the classical archetypes you mention, as well as mythology, could have went into it as well. It can be more than one thing!

Bravo. Bien dit.

Pingback: Black Panther Too Political? History Says No – ComicCritter

It’s excellent to discover some sort of weblog each and every every now and then that will isn’t the identical expired rehashed stuff. Great read!

Pingback: Christopher B. Zeichmann

I apologize for this being so late, but my problem with the idea is, well, Stan Lee a) was never a particularly deep political thinker and b) had an unfortunate tendency to retcon his own self mythology. Most of the nuance to Magneto’s character comes from writers like Chris Claremont. The idea of a civil rights struggle for mutantkind just was not present in the early X-Men comics. As well, Magneto is a fairly cardboard villain with plans for world domination. It’s also notable that while many have commented on the contrast between Xavier’s and MLK’s methods, I don’t think their goals are similar either. Xavier doesn’t seem as much concerned with integrating mutants into human society as protecting and guiding young mutants. He’s more Dumbledore than MLK.

Really, however, the main problem I have with this is that while Stan was many things, political was not one of them. He expressed standard liberal views on prejudice, but he never strayed from the status quo on issues like US militarism. (Iron Man used stereotypical Chinese and Vietnamese villains in the origin story, and Stan never really criticized the war in Southeast Asia).

Finally, the simple fact is that Stan didn’t have much time to think about Magneto one way or another, as he stopped writing the series by issue #20.

Hecka late response but.. I don’t think we disagree that much. Stan’s relationship to the civil rights themes in X-Men are indeed nebulous. I simply ponder how much he may have absorbed those themes as background noise. What I try to point out, however, is that they are much more firmly grounded during the Claremont era. I tend to lean towards the notion of a later Stan Lee “retconning” and claiming a similar inspiration for the sake of presenting a continuity in the comic–which probably wasn’t actually there. Certainly, however, by the Claremont era, they were loud and intentional–and probably helped make the comic as popular as it is today. Excelsior!

I mean, it’s hard to dislike Stan (unless you’re Jack Kirby or his family) but he just wasn’t that deep a thinker.

Also, I feel that people downplay the risks Claremont took, especially with God Loves Man Kills. Making Magneto sympathetic was a big deal at the time, and I swear that there was at least a bit of pushback against this.

Oh I’m sure showing Magneto at his most Malcolm X-esque as he gazes over the bodies of lynched Black children’s bodies in a playground was a VERY big deal for its day. Claremont was definitely taking risks he couldn’t know would pay off. But for me, as a Black kid reading that book, it meant EVERYTHING.