In the bleakest of moments African-American writers have turned to literature to confront racial terror and the trauma it could induce–turning to poetry, personal narratives, plays and novels. Sometimes, they even dreamed of the fantastic.

In the bleakest of moments African-American writers have turned to literature to confront racial terror and the trauma it could induce–turning to poetry, personal narratives, plays and novels. Sometimes, they even dreamed of the fantastic.

“When I get mad, I write it down on a pad.”–Chuck D

In the wake of the Charleston shooting, I asked a fellow black speculative fiction enthusiast if he planned to write through this tragedy. “Always,” he replied without missing a beat. “Yes.”

Literature has long been a place where black anger, grief and trauma could be poured onto pages when denied a voice or recognition in the more traditional public sphere–from early slave narratives to the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance up to modern day. And speculative fiction, that ability to imagine beyond the confines of our mundane world, has been a part of that story.

Last December, in the wake of the Ferguson verdict that saw no charges for the unarmed killing of teenager Mike Brown, activist Walidah Imarisha popularized the term “visionary fiction” to describe the use of “science fiction, horror, and fantasy genres to envision alternatives to unjust and oppressive systems.” Imarisha contends that speculative fiction is “a perfect testing ground” to explore alternatives to a world of police abuse, social inequity, a prison industrial complex and the overall violence and neglect by the state with regards to black communities. In a similar sense, speculative fiction has also been a refuge for black writers seeking to deal with incidents of racial terror in their midst–a means to confront the traumatic by interpreting it through the fantastic.

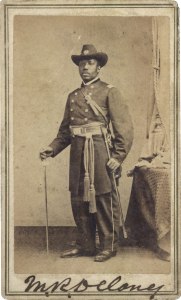

In the 1850s, in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision, black abolitionist Martin R. Delany serially published a set of stories in the free black Anglo-African Magazine in 1859; they were republished in the Weekly Anglo-African in 1861 and 1862. The stories amounted to a novel called Blake; or the Huts of America. In it, Delany’s main character Blake is a slave revolutionary who dreams of creating a free black country in Cuba. Blake serves as a counter to the most popular black character in antislavery literature at the time, Uncle Tom, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

In the 1850s, in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision, black abolitionist Martin R. Delany serially published a set of stories in the free black Anglo-African Magazine in 1859; they were republished in the Weekly Anglo-African in 1861 and 1862. The stories amounted to a novel called Blake; or the Huts of America. In it, Delany’s main character Blake is a slave revolutionary who dreams of creating a free black country in Cuba. Blake serves as a counter to the most popular black character in antislavery literature at the time, Uncle Tom, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Delany is also, amazingly, writing this in the very year radical abolitionist John Brown (with whom Delany was intimately acquainted; he attended Brown’s Convention just a year earlier) makes his fateful raid on Harper’s Ferry to stir up a slave rebellion. In its radical imagining of a nation-wide slave revolt, Delany confronts not only the institution of human bondage but the everyday racial terror and trauma that free black communities endured with slavery still firmly entrenched in American society. For black Northern communities who lived through constant fears of kidnappings in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act, anti-black riots, pervasive racism, laws like the Dred Scott decision that denied their humanity, and an encroaching slave power that posed an ever-present existential threat, Blake was an attempt to imagine other possibilities.

In 1892, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, an abolitionist, writer and poet born to free black parents, published her novel Iola Leroy. The story follows the life of a mixed-race woman who through slavery into emancipation and Reconstruction. Throughout, Iola must deal with issues of race and gender as she passes through both black and white worlds; the book ends with her articulating her idea of an ideal polity, made by free African-Americans in a New South.

In 1892, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, an abolitionist, writer and poet born to free black parents, published her novel Iola Leroy. The story follows the life of a mixed-race woman who through slavery into emancipation and Reconstruction. Throughout, Iola must deal with issues of race and gender as she passes through both black and white worlds; the book ends with her articulating her idea of an ideal polity, made by free African-Americans in a New South.

The story is a startling confrontation of race in the 1890s, the era of the Nadir–considered the lowest point of race-relations in the United States, as anti-black riots, lynching, terrorism and disfranchisement ruled alongside a near nation-wide Jim Crow orthodoxy. This followed the willful killing of Reconstruction, and the establishment of an apartheid regime based on white supremacy throughout the South–through acts of relentless violence, political assassinations and massacres. As one Alabama Southern news editor warned, “We will render this a white man’s government, or convert the land into a Negro man’s cemetery.”

This was the world that as a black woman Harper would have confronted. She would have been witness to the Southern horrors that moved contemporaries like Ida B. Wells-Barnett to write her treatise on American lynching, A Red Record. Throughout her life, Harper was a social reformer and held out hope for bi-racial cooperation through popular women’s movements. She joined the white-led National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in 1883 for its social reform and advocacy of gender equality, but left in 1890, disappointed that it did not focus on black issues like anti-lynching law, civil rights, or abolishing the notorious convict lease system. In 1894 Harper helped found The National Association of Colored Women as an alternative, and in 1897 served as its president.

As a character, Iola Leroy’s life of crossing racial and gendered boundaries in search of a more perfect society, in some ways mirrors Harper’s search for the same. As an abolitionist in the 1850s, Harper had also been in contact with figures like John Brown and worked with both the Anti-Slavery Society and Unitarian Church. In many ways the utopian vision articulated by Iola Leroy was Harper’s own voice, her confrontation of the tragedy and terror of the Nadir. Iola’s ideal polity offers a hope for a better world, one that was missing in her own reality.

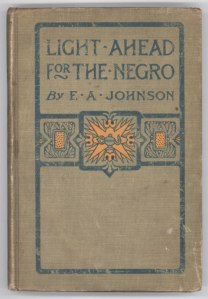

Harper wasn’t the only one imagining utopias that challenged the racism and marginalization of the age. In 1904 black educator and lawyer, and later politician, Edward A. Johnson, wrote Light Ahead for the Negro. The story is told from the point of view of a black protagonist, the son of an abolitionist. Traveling by airship (steampunk enough for you?) he suffers a mysterious accident that lands him one hundred years in the future–in 2006. There, he finds that the South has undergone drastic transformation. African-Americans, allowed to attend schools, have excelled and become members of society. Though it is not a perfect world, it is a vision of a utopia that is steadily working to move beyond race.

Harper wasn’t the only one imagining utopias that challenged the racism and marginalization of the age. In 1904 black educator and lawyer, and later politician, Edward A. Johnson, wrote Light Ahead for the Negro. The story is told from the point of view of a black protagonist, the son of an abolitionist. Traveling by airship (steampunk enough for you?) he suffers a mysterious accident that lands him one hundred years in the future–in 2006. There, he finds that the South has undergone drastic transformation. African-Americans, allowed to attend schools, have excelled and become members of society. Though it is not a perfect world, it is a vision of a utopia that is steadily working to move beyond race.

To put Johnson’s work in perspective, the early 1900s was an exceedingly violent time for African-Americans. Seventy-six black persons were lynched in 1904 alone. In the next ten years, close to 900 black men, women and children would be lynched across the nation–with no abatement in sight, and little to no regard or recourse from state and federal authorities. Some of the most destructive anti-black race riots would engulf cities like Atlanta, Georgia and Springfield, Illinois–with white mobs killing blacks by the score, destroying black property and sending hundreds fleeing. This was sheer racial terror, a living trauma, from which for many there seemed no relief.

Johnson’s aptly named work sought to imagine a future light where for many it seemed there was none: hope for the seemingly hopeless. In his foreword he makes an appeal, pointing out that two factions are striving for control of the South–one that would “crush” blacks into a state of “serfdom” and another more sympathetic to their plight. Johnson dedicates his book to this latter group, in a way offering white society a way out of the trauma of racism and hatred it has created for itself.

If Johnson offered a peaceful hope for a post racial future, author and Baptist Minister Sutton E. Griggs’s earlier 1899 work Imperium in Imperio: A Study of the Negro Race Problem was a work in contrast. The 1890s had seen an average of 100 blacks lynched per year, and anti-black riots and pogroms that destroyed black lives and communities. Confronting this ceaseless violence through imagination, Griggs weaves a tale of a shadowy secret black government in Waco, Texas, determined to mount an armed revolt to conquer the state and create a free black homeland.

If Johnson offered a peaceful hope for a post racial future, author and Baptist Minister Sutton E. Griggs’s earlier 1899 work Imperium in Imperio: A Study of the Negro Race Problem was a work in contrast. The 1890s had seen an average of 100 blacks lynched per year, and anti-black riots and pogroms that destroyed black lives and communities. Confronting this ceaseless violence through imagination, Griggs weaves a tale of a shadowy secret black government in Waco, Texas, determined to mount an armed revolt to conquer the state and create a free black homeland.

Most of the story follows the contested relationship between two allies with different perspectives on the tactics for black advancement, as they vie for the fate of the organization and its direction. Griggs fantastic dream of an “empire within an empire,” who foments rebellion beneath the very noses of white authority, will predate satirist and journalist George Schuyler’s similarly themed Black Empire–with the shadowy “Black Internationale” and the mad scientist Dr. Belsidius–by some thirty years.

Terror and trauma did not always take the form of the rope, and mob and destructive fire. White supremacy during this time period in America was entrenched and structural, pervading nearly every aspect of society–from popular media to academic disciplines. This was an era where scientific racism was normalized, used as justification for the inherent “superiority of whites” and the “inferiority” of all “others.” Popular scientific and historic treatises declared blacks as beings of weak intellect, with a past rooted in “savagery.” In 1906, an African man named Ota Benga was even exhibited in the Bronx Zoo–as a type of ape, part of a larger global trend of dehumanization.

Britain’s John Bull and Uncle Sam take up “The White Man’s Burden,” 1899–part of a larger policy of invasion, colonization, subjugation and globalized racial terror.

Britain’s John Bull and Uncle Sam take up “The White Man’s Burden,” 1899–part of a larger policy of invasion, colonization, subjugation and globalized racial terror.

European Empires utilized this racial ideology as part of the colonial impulse that would carve up and subjugate much of the known at the barrel of the Maxim. The U.S. went through its own colonial period, exporting its brand of racialized terror–now backed with military might–to Hawaii, the Philippines, Central America, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and elsewhere. Anti-blackness was part of all of these ventures, with the “darker” subjugated races of the world often portrayed in American media as unruly, unkempt, black children–a version of the brutal Picaninny stereotype–in need of supervision.

Born in 1859 to free black parents in Maine, writer Pauline Hopkins sought to challenge much of this within her works in the early 20th century. Best known for her short stories between 1900 and 1903, she also self-published a 1905 pamphlet titled “A Primer of Facts Pertaining to the Early Greatness of the African Race and the Possibility of Restoration by Its Descendents.” Hopkins firmly believed that African-Americans needed to link themselves to a past that would counteract the racism of the age. History was the discipline to do this, and she would find ways to weave it into her fiction as well–with fantastic results.

Born in 1859 to free black parents in Maine, writer Pauline Hopkins sought to challenge much of this within her works in the early 20th century. Best known for her short stories between 1900 and 1903, she also self-published a 1905 pamphlet titled “A Primer of Facts Pertaining to the Early Greatness of the African Race and the Possibility of Restoration by Its Descendents.” Hopkins firmly believed that African-Americans needed to link themselves to a past that would counteract the racism of the age. History was the discipline to do this, and she would find ways to weave it into her fiction as well–with fantastic results.

In 1903, Hopkins published a serial of short stories in the magazine Colored American (which she would later take over as editor) called Of One Blood; Or, The Hidden Self. Subverting the tropes of white supremacy and black inferiority, the stories follow an African-American named Reuel Briggs. Raised on the racism so pervasive in America, Briggs has come to believe in his own inferiority and has little concern of the black past. This changes when he travels to Ethiopia and finds the lost 6000 year old ancient city of Telessar, which uses futurist technology based on crystals, suspended animation and a means of telepathy. The novel is one of the first by an African-American that uses an African setting, and pulls on historical romance, science fiction, fantasy and mystery to confront–and in some ways overthrow–white supremacy. As Hopkins herself stated, the story was intended to “raise the stigma of degradation from [the Black] race.”

In 1920, activist and scholar W.E.B. DuBois did not confront the dismal realities of ever pervasive racism and violence with utopia, but dystopia. In DuBois’s story “The Comet,” New York City has been destroyed by a comet that releases toxic gasses that kill off nearly everyone. A black man, Jim Davis, and a wealthy white woman, Julia, are left to pick up the pieces. Throughout the story we’re treated to poignant scenes, such as Jim entering an emptied diner where he would have before been refused service. He and Julia are allowed to explore their relationship beyond the tensions of race, at least for the moment when they think they may be the only people left.

In 1920, activist and scholar W.E.B. DuBois did not confront the dismal realities of ever pervasive racism and violence with utopia, but dystopia. In DuBois’s story “The Comet,” New York City has been destroyed by a comet that releases toxic gasses that kill off nearly everyone. A black man, Jim Davis, and a wealthy white woman, Julia, are left to pick up the pieces. Throughout the story we’re treated to poignant scenes, such as Jim entering an emptied diner where he would have before been refused service. He and Julia are allowed to explore their relationship beyond the tensions of race, at least for the moment when they think they may be the only people left.

DuBois’s story is profound in its timing. It comes out just five years after the release of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, a film that revolves around a caricature of black brutish sexuality and the purity of white womanhood threatened. It was a hit with American audiences, even receiving a viewing at the White House and quoting the southern president Woodrow Wilson, who enforced draconian Jim Crow laws in Washington DC itself. By 1920, the film had helped reinvent and revitalize the Ku Klux Klan–which had gone from a few thousand scattered, disorganized members to a politically powerful force of more than 4.5 million. The years between that time had been exceedingly violent for African-Americans. One of the bloodiest anti-black race riots in the nation’s history erupted in East St. Louis in 1917, in the days before July 4th. For three days, rioting white mobs destroyed entire blocks of African-American homes and businesses, injuring hundreds and driving some 6,000 blacks from their homes; a Congressional committee estimated that between 40 to 200 people were killed. This would all culminate in the infamous Red Summer of 1919, as anti-black race riots swept through over three dozen cities across the United States.

DuBois himself had been witness to enough of this violence, which he documented consistently in the media arm of the NAACP The Crisis–much of it pulled from the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett. He had also lived through it. In 1899 when the black laborer Sam Hose was lynched by a 2000 strong white mob in Atlanta, DuBois intended to send a measured and even-handed letter to the local Atlanta newspaper to register his protest. On his way there he was informed Hose’s charred, severed and bloody knuckles–a souvenir from the lynching where such rituals were common–sat on display in a local grocer’s butcher shop. It was too much. A shaken DuBois turned about and went home, never delivering the letter. “One could not be a cool, calm and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched,” he later recounted.

“The Comet” confronts these many racial terrors, giving us an even greater terror in the form of an apocalypse. It even plays with the tensions of race and sexuality that were so taboo at the time, and which could incite such terrible violence. In the dystopia that’s left in the comet’s wake there’s the possibility that a new world is being formed, but only with the utter destruction of the old one.

As we attempt to comprehend the events and issues of our day, looking back at some of these works may prove instructive. Confronting racial terror now, as then, may require us to journey beyond the mundane and explore new imaginative ways to give voice to our anger, our grief, frustration and hopes.

References and further reading:

Maria Giulia Fabi, “Race Travel in Turn-of-the-Century African-American Utopian Fiction,” in Passing and the Rise of the African American Novel (Champaign: University of Illinois, 2005).

Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Knopf, 1998).

Nadia Nurhussein, “The Hand of Mysticism”: Ethiopianist Writing in Pauline Hopkins’s Of One Blood and the Colored American Magazine, Callaloo Volume 33, Number 1, Winter 2010 pp. 278-289.

Reiland Rabaka, W.E.B. Dubois’s “The Comet” and Contributions to Critical Race Theory: An Essay on Black Radical Politics and Anti-Racist Social Ethics, Ethnic Studies Review 29.1 (Summer 2006): 22-III.

Sheree Renee Thomas, ed. Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (New York: Warner Books, 2000).

Reblogged this on John Edward Lawson and commented:

I was lucky enough to experience Phenderson dropping knowledge in person during a presentation at the Enoch Pratt Free Library back in February. Please take a moment to read what he has has to say about the present, and the past. Thank you.

Wow….i like it

Reblogged this on nigelfungai's Blog.

Thank you for this piece.

Pingback: Of Interest (March 13, 2016) | Practically Marzipan

Pingback: For the Good of the Order: Writing Goals 2017 | Phenderson Djèlí Clark

Pingback: Writing SFF in the Resistance | Phenderson Djèlí Clark

Pingback: Tips for Understanding Black History Month- 2017 RESIST Edition | Phenderson Djèlí Clark

Pingback: EP 10 Filmmaker M. Asli Dukan - Contemporary Black Canvas

Pingback: Tips for Understanding Black History Month- 2018 Wakanda Edition | Phenderson Djèlí Clark

Pingback: Tips for Understanding Black History Month- 2019 Wakanda Redux Edition | Phenderson Djèlí Clark

Pingback: Tips for Understanding Black History Month- 2020 Edition | Phenderson Djèlí Clark

Pingback: Writing Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos | Phenderson Djèlí Clark